Migraine is a complex neurological disorder often characterized by severe headache. It is marked by the frequent presence of nausea and/or hypersensitivity to various stimuli, such as noise, light, odors, and sometimes even a gentle touch to the scalp. This makes it a highly debilitating condition that, unfortunately, responds very variably to different therapeutic options. A migraine attack can last for several hours, or even several days, and the associated pain is often described as a pulsating pain, akin to throbbing. In general, it is unilateral, but it may also be felt across the entire head or touches the sides of the head alternatively. Other migraine symptoms vary depending on the type of migraine. The frequency of a migraine attack can vary from 2 to 3 episodes per year to more than one episode per week. Migraines are labelled chronic when the attacks occur at least 15 days per month.

Migraine is not a recent phenomenon. The earliest known writings resembling descriptions of migraines date back to around 3000 BCE in Mesopotamian poems. Much later, Hippocrates mentioned visual disturbances that sometimes precede unilateral head pain. He advocated for pharmacotherapy in treating this affliction and also noted that inducing vomiting could sometimes provide relief. Although Aretaeus is credited with the discovery of migraine in the 2nd century, it was Thomas Willis in 1672 who wrote the first modern treatise on migraine, proposing a vascular origin through the dilation of cranial blood vessels.

The techniques used for treatments, however, remained particular. For example, Erasmus Darwin, the grandfather of Charles Darwin, in the late 1700s, suggested placing the patient in a centrifuge to move blood from the head to the feet.

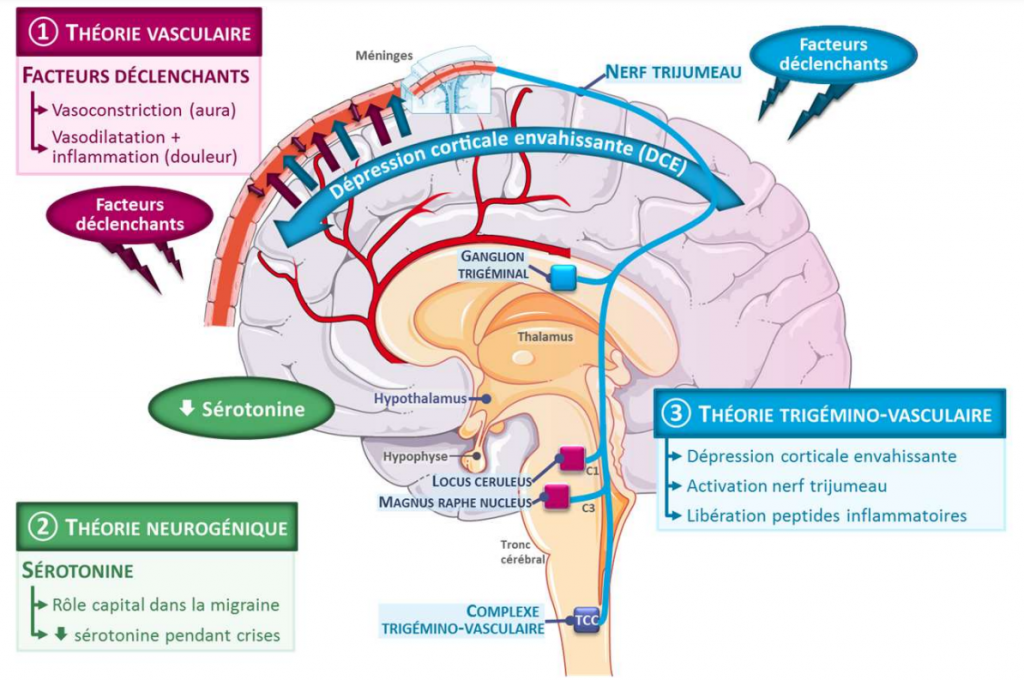

In the late 1800s, some writings mention the antimigraine effect of extracts from ergots on rye (a poisonous fungus). In 1918, ergotamine was isolated from ergot, and in 1938, John Graham and Harold Wolff demonstrated that ergotamine works through vasoconstriction, thus supporting the vascular theory of migraines. In 1943, dihydroergotamine was synthesized and began to be prescribed almost immediately at the renowned Mayo Clinic. Finally, another class of medications, the triptans, made their appearance in the early 90s with the birth of sumatriptan.

However, it became clear through conducted studies that the vascular cause did not hold up. There are indeed vascular changes that accompany migraines, but these follow neurological changes. Michael Moskowitz proposed the trigeminovascular theory of migraine, suggesting that migraine pain is linked to inflammation of the walls of the vessels at the base of the brain.

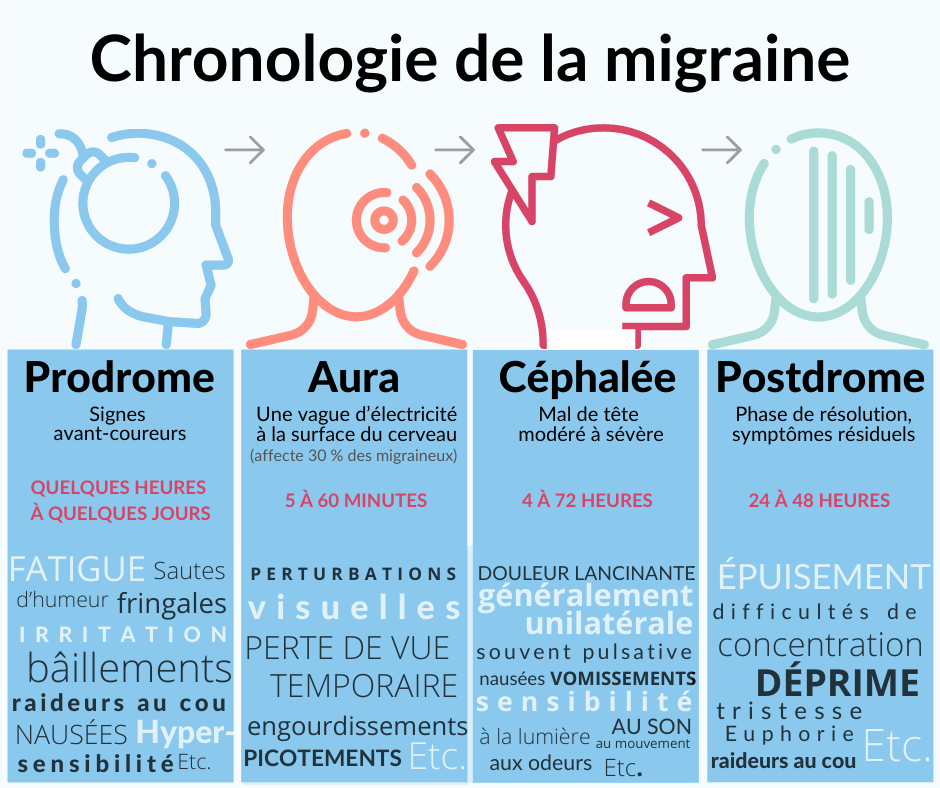

The symptoms experienced during a typical migraine attack depend on the stage within the attack. Firstly, in the hours preceding the attack, there is often a prodrome, a phase during which the person feels that an attack is impending. Next, some individuals will experience an aura, most commonly visual, which can last up to an hour. Gradually, the aura dissipates, giving way to the headache, which can last between 4 and 72 hours. Finally, many people suffering from migraines will also experience a postdrome.

Prodrome

Approximately 30% of migraineurs report symptoms before the onset of the headache, which can accurately predict the onset of the migraine in the following hours. Precursor symptoms can be very diverse. The most common ones include fatigue, neck stiffness, gastrointestinal disturbances, yawning, nausea, increased frequency of urination, and difficulty concentrating.

Aura

It is also 30% of migraine afflicted people who will experience an aura. It precedes the migraine attack and can manifest as:

-Visual disturbances in the majority of cases, which can be characterized by the appearance of bright spots in the field of vision (scintillating scotoma);

-Sensory disturbances that can manifest as tingling or numbness;

-Language disturbances with difficulty or inability to speak.

Cephalgia

The pain of a migraine is typically unilateral and often varies from one side to the other during an attack. It is mainly felt in the frontal, temporal, and ocular regions. There is also usual pain in the cervical and occipital regions, and sometimes in the vertex region (top of the head).

Typically, the pain is similar to a pulse or a throb. The intensity is from moderate to severe, and almost invariably (95%), there is an exacerbation of pain by routine physical activities, such as walking and climbing stairs. Moreover, about 50% of migraineurs will report photophobia or phonophobia, 80% nausea, and 50% vomiting. The intensity of associated symptoms is usually proportional to the severity of the attack.

Postdrome

The postdrome is often compared to a hangover or a zombie-like sensation. These phase mainly includes fatigue and difficulty concentrating. It can last up to two days after the painful crisis.

Several triggering factors, often referred to as “triggers,” are well-known for their ability to induce an attack in a person with migraines. The presence of triggers has been reported by 90% of those with migraines. Stress and anxiety are the most common causes. There is also causes in nutrition, alcohol, menstrual cycles, strong smells (from perfum or certain flora), fatigue and lack of sleep, and changes in the temperature. It’s worth noting that this list is by no means exhaustive, and triggers vary widely from one individual to another. Indeed, a meta-analysis involving more than 27,000 subjects suffering from primary headaches actually identified over 400 unique triggers. Keeping a daily journal can help identify these triggers. Finally, it should also be noted that triggering factors may sometimes manifest only during a vulnerable period or in combination with another trigger. For example, a person with migraines may experience an attack after consuming alcohol during the menstrual period, while in other circumstances, it may not necessarily have an impact.

Migraine is a common condition, with a prevalence of 14 to 25% in adult women and 7 to 9% in adult men. However, before puberty, the tendency is reversed, with a slightly higher prevalence in males, peaking between 6 and 10 years of age, while in females, the incidence is higher between 14 and 19 years. In fact, about 5 to 8% of children in school years complain about headaches, hindering them at least partially in their activities.

In Canada, 2.7 million individuals are estimated to be diagnosted with migraines; that is the entire population of Toronto. Migraines transitions into chronic migraines in approximately 8% of migraine cases, affecting a total of 1 to 2% of the population. Concerning auras, it seems that about 20% of migraine cases have them.

As migraines can be highly debilitating due to the severity of pain and associated symptoms, they have a significant impact on family relationships and society as a whole. For example, in Canada, indirect costs related to absenteeism at work and reduced productivity amount to up to 900 million dollars per year. Evidently, migraines equally have an enormous impact on the life’s quality of the person sufferent from this affliction. Approximately 3% of migraineurs report very high disability as defined by the Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (MIDAS), whereas in the case of chronic migraineurs, the proportion increases to 25%.

Finally, migraine is associated with a multitude of comorbid conditions including epilepsy, mental disorders such as anxiety and depression, certain allergies, hypertension, and strokes (cerebrovascular accidents), to name a few. In fact, up to 17% of strokes below the age of 50 could be related to migraine. A literature review has also recently demonstrated an increased prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in migraine sufferers. There also appears to be a connection with other gastrointestinal conditions as well as asthma. The mechanisms underlying these latter links, however, are mostly more or less well understood.

Our understanding on migraine mechanics are developping, although many unresolved questions remain. Migraine is due to abnormal neuronal excitability, as is the case with epilepsy or certain movement disorders (e.g., paroxysmal dyskinesias). This phenomenon is itself linked to a genetic predisposition, modulated by environmental factors (hormones, stress, food, etc.).

While it is still unknown how a migraine attack is triggered, the role of the hypothalamus has been confirmed by imaging: it could be a “generator” of migraine attacks.

Furthermore, significant progress has been made in understanding the mechanisms involved in the various associated symptoms. Thus, the migraine aura is probably caused by a transient dysfunction of the cortex that leads to a slow wave of depolarization of neurons from the back of the brain to the front. We talk about “spreading cortical depression” (SCD). This phenomenon can be observed through functional imaging during spontaneous migraine attacks with aura. It leads to a transient decrease in neuronal activity, with a slight decrease in cerebral blood flow. This explains the visual, sensory, language-related, or motor weakness neurological symptoms experienced by patients. In the case of familial hemiplegic migraine, known mutations have the same consequences: an increase in potassium and glutamate in the synaptic cleft that separates two neurons, leading to neuronal hyperexcitability and increased sensitivity to spreading cortical depression.

The migraine headache is secondary to the dilation and inflammation of cerebral vessels, especially those in the meninges on the brain’s surface. These changes are provoked by the abnormal activation of the trigeminovascular system, which innervates the meningeal vessels and induces nerve stimulation through the release of CGRP, “pain messenger” neuropeptides.. There is also abnormal activation of neurons in the brainstem and hypothalamus, contributing to the initiation, amplification, and/or persistence of the pain signal. Some animal studies have shown that waves of SCD could trigger the activation of the trigeminovascular system, suggesting a link between aura and migraine headache for patients with migraines with aura.

It was commonly accepted since the 1940s that intracranial pain sensitivity was limited to the dura mater, the outermost meningeal membrane lining the skull’s vault and base, and its nourishing vessels. Thus, the dilation and inflammation of the arteries in the dura mater were originally considered the cause of the pain associated with migraines. However, a clinical study conducted by French researchers and neurosurgeons has recently revised this concept by demonstrating that the pia mater, located beneath the dura mater, and its nourishing vessels are also sensitive to pain. These structures could also be involved in the cephalgia.

In previous generations, migraines were often primarily considered issues related to brain vasculature, leading to frequent reliance on medication as a primary form of treatment. However, recent research over the past decade has unveiled a more nuanced understanding, acknowledging that migraines can be influenced by various factors, including neurological, vascular,

environmental, and musculoskeletal elements.

At the clinic La Migraine, Dr. Daniel Lachance, chiropractor, advocates for an approach that recognizes the correlation between migraines and cervical issues. His treatments, which prioritize addressing cervical problems, have yielded

impressive results, contributing to a progressive understanding of the complex nature of migraines and their potential treatments.